What Is TAM?

Big ideas feel exciting—until someone asks for TAM, and my story suddenly needs math.

TAM (Total Addressable Market) is the total revenue opportunity for a product if it captured 100% of a defined market. I use TAM to frame the ceiling of an opportunity, then I narrow it into something I can actually win.

I treat TAM like a “market voice” signal: it tells me how big the playground is, not how many toys I will take home.

What Is TAM?

TAM is the maximum potential demand for a product in a defined market, usually expressed as annual revenue. The phrase “defined market” is the whole game. If I define the market too broadly, TAM becomes a fantasy number. If I define it too narrowly, TAM can hide a real opportunity. So I always state the boundary in one sentence before I show any number:

(1) Product + use case (what exactly is being bought?)

(2) Buyer type (who is paying?)

(3) Geography (where?)

(4) Time window (per year is most common)

(5) Pricing basis (subscription, transaction, seats, usage)

When I do this, TAM becomes a useful planning input instead of a “pitch number.” On voicesfromtheblogs.com, the whole vibe is decoding messy market signals into clear decisions. TAM is one of those decisions—because it forces clarity about who the market really is.

Why Does TAM Matter?

TAM matters because it tells me whether the opportunity can support my goals and what kind of strategy makes sense. If TAM is small, I usually need a premium model, a tight niche, or strong retention. If TAM is large, I might still fail if the market is crowded or the buyer is expensive to reach. So I never use TAM alone. I use it as the top boundary, then I ask more practical questions.

Here is what TAM helps me do in real life:

(1) Pick battles: I stop chasing markets that cannot support the effort.

(2) Set expectations: I avoid unrealistic revenue targets.

(3) Choose a go-to-market path: enterprise vs self-serve looks different depending on market shape.

(4) Explain the business: investors and partners want a consistent market frame.

(5) Spot a wedge: a big TAM can hide a very winnable first segment.

At the same time, I keep one rule: TAM is not what I will earn. TAM is the “ceiling,” not the forecast. My forecast comes from reachable segments, channels, and conversion reality.

How Do You Calculate TAM?

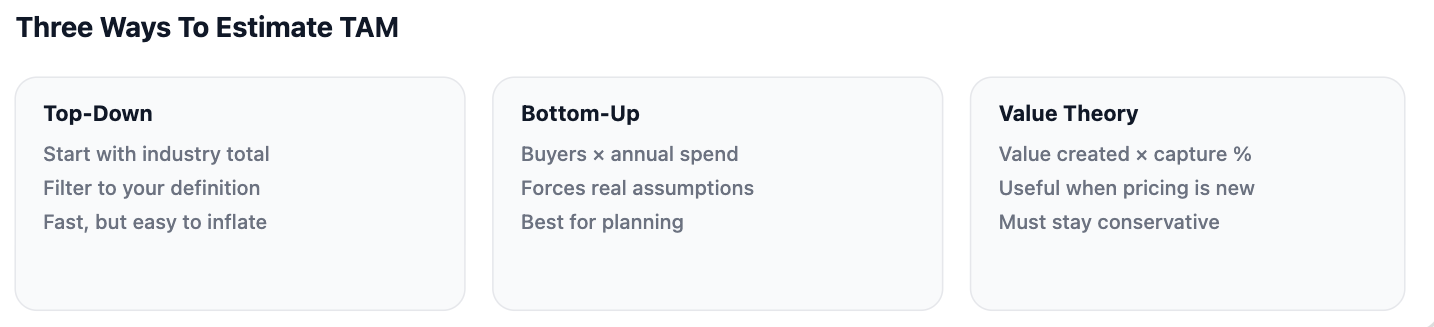

I calculate TAM by choosing a method and building a simple model with assumptions I can defend. The math should be explainable in a minute. If I need ten minutes, my assumptions are probably fuzzy.

What Is The Top-Down TAM Method?

Top-down TAM starts with a published market number and narrows it to my definition. I use it when good market research exists, but I stay cautious because filters can be abused. I keep the filters few and obvious.

A clean top-down pattern looks like:

(1) start with total category revenue

(2) narrow by geography

(3) narrow by segment and use case

(4) sanity-check with real buyer counts and pricing

If my filtered TAM implies “every company buys twice,” I know the model is lying.

What Is The Bottom-Up TAM Method?

Bottom-up TAM builds from real units: number of buyers × annual spend per buyer. This is my favorite because it forces me to define the buyer and the pricing anchor.

Bottom-up structure:

(1) count target customers in the market boundary

(2) estimate % that actually has the need

(3) estimate realistic annual spend (or ACV / ARPU)

(4) multiply to get TAM

I like bottom-up because it surfaces what I do not know. If I cannot estimate customer count or spend, I do not understand the market yet.

What Is Value-Theory TAM?

Value-theory TAM estimates what customers would pay based on value created. I use it when pricing is not standard or outcomes are measurable (time saved, cost reduced, revenue increased). I estimate value per customer, then estimate a realistic share of that value customers pay, then multiply by customers with that problem.

I keep value-theory conservative because it is easy to exaggerate. If the value claim is not believable, the TAM is not believable.

What Is The Difference Between TAM, SAM, And SOM?

TAM is the total market ceiling, SAM is the serviceable portion you can target, and SOM is the realistic share you can win. I like this trio because it prevents me from confusing “big market” with “reachable revenue.”

I define them like this:

(1) TAM: everyone in my defined market who could buy, at full scale

(2) SAM: the part I can actually serve given product scope, geography, and constraints

(3) SOM: the share I can realistically capture in a set time window with my channels and competition

In practice, I use TAM to set the category story, SAM to set strategy focus, and SOM to set near-term forecasts. If I only talk about TAM, I sound vague. If I only talk about SOM, I may undersell the opportunity. The best plan connects all three with one clean bridge: what changed in the market, what it does to customers and competitors, and how it alters my plan.

What Are Common TAM Mistakes?

The biggest TAM mistakes are defining the market too broadly, confusing interest with intent, and hiding assumptions. These are the traps that make TAM look impressive but useless.

Mistakes I actively avoid:

(1) “Everyone” markets: using population as demand

(2) Category inflation: claiming the whole category even when my use case is narrow

(3) No time window: mixing monthly and annual numbers

(4) Unrealistic pricing: using premium ARPU for budget buyers

(5) Ignoring substitutes: assuming customers switch instantly from “do nothing”

(6) No sanity checks: not testing implied buyer counts and spend

My quick sanity check is simple: if my TAM implies an impossible number of buyers or an unrealistic spend per buyer, I redo the assumptions.

Conclusion

TAM is the total market ceiling, and it only helps when I define the market clearly and show honest assumptions.