What Is Market Potential?

Big plans fail when the market is “huge,” yet nobody can prove the demand.

Market potential is the maximum demand (sales or revenue) that could exist for a product in a specific market, under reasonable conditions.

I treat it as the ceiling for opportunity, then I work backward into what I can actually win.

What Is Market Potential?

Market potential is the upper limit of how much a market could buy if the offer and conditions are right. I do not confuse it with what my company will sell. I treat it as “how big could this get” for a defined market, with clear boundaries. Those boundaries matter more than the number. If I don’t define the market, the number is just a vibe.

Here’s how I define the market so the estimate stays useful:

-

Who: one customer type (not “everyone”)

-

Where: one geography or channel scope

-

What: one product category or use case

-

When: one time window (often 12 months or 3 years)

Then I state what “potential” means in that context: units, customers, or revenue. I prefer revenue because it connects to business plans, but I still sanity-check with units so I don’t hide behind dollars.

This topic fits voicesfromtheblogs.com naturally because market potential is basically a “signal decoding” problem. The Market voice asks what demand could exist. The People voice asks who truly wants it and why. Then the Strategist voice turns that into a number I can plan against.

Why Does Market Potential Matter?

Market potential matters because it prevents me from building a plan on wishful thinking. If I skip this step, I tend to overbuild product, overspend on marketing, or pick the wrong segment. If I do the step well, I can size the prize, then decide if the effort makes sense.

I use market potential to answer practical questions like:

-

🧭 Is the opportunity worth it? If the ceiling is small, I need a higher margin or a cheaper go-to-market.

-

💰 How should I price? If the market potential is high but the spend per customer is low, I may need volume and low friction.

-

🧪 What should I test first? I test the biggest uncertainty behind the estimate, like willingness to pay or adoption rate.

-

🧱 What does “success” look like? If the ceiling is $5M/year, then a $50M story is not credible.

This is where I like the VOICES mindset: when the market potential number feels shaky, it usually means one of the “voices” is missing. I either don’t understand the market structure, or I don’t understand buyer behavior, or I don’t have a clear strategy scope.

What Is The Difference Between Market Potential And Market Size?

Market size is what the market is doing now, while market potential is what the market could do at its ceiling. Market size answers “how big is it today?” Market potential answers “how big could it be if adoption expands or conditions improve?”

I keep this simple with a mental ladder:

-

Market Size (today): current demand in the defined market

-

Market Potential (ceiling): maximum plausible demand in the defined market

-

My SOM (winnable): the share I can realistically obtain

This distinction stops a common confusion: people grab today’s market size and call it potential, or they grab total potential and call it a forecast. I don’t do either. I treat potential as the ceiling, then I build my plan with conservative capture assumptions. If someone challenges me, I can show the logic instead of defending a random number.

How Do I Estimate Market Potential?

I estimate market potential by using two methods, then I force them to agree within a reasonable range. I do not hunt for one “correct” number. I build a defendable range.

How Do I Use A Top-Down Estimate?

I use top-down when I want speed and a sanity check. I start with a credible big number (industry/category), then I narrow it by segment, geography, and use case. The risk is that top-down can hide weak assumptions. So I keep my narrowing steps visible and simple.

My top-down steps:

-

Start with category demand

-

Narrow to my segment

-

Narrow to my region/channel

-

Apply an adoption/fit rate

How Do I Use A Bottom-Up Estimate?

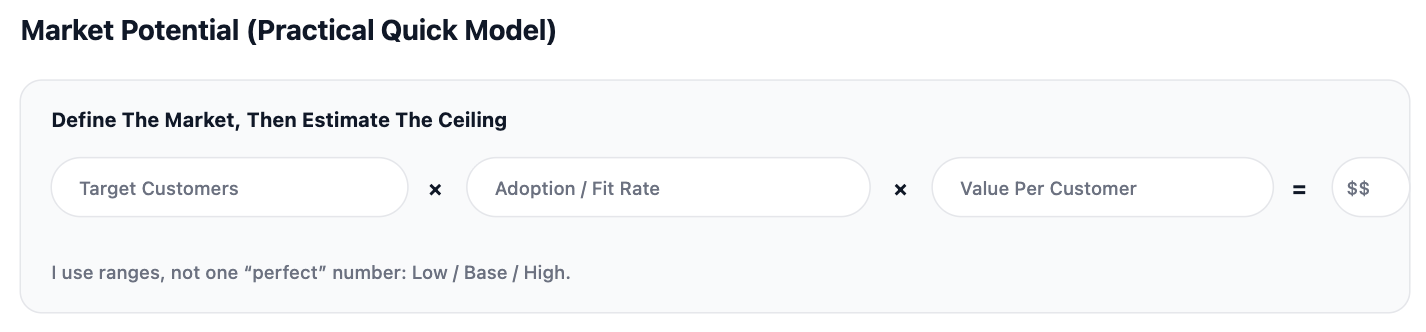

I use bottom-up when I want realism and planning value. I count target customers I can actually reach, then multiply by expected adoption and value per customer.

My bottom-up steps:

-

Count target customers (in my defined market)

-

Estimate adoption/fit rate (low/base/high)

-

Estimate value per customer (ARPA or annual spend)

-

Multiply into a range

Bottom-up is slower, but it becomes a planning tool. It also maps cleanly into SAM and SOM later.

What Mistakes Should I Avoid?

I avoid mistakes that make the number look “big” but make the plan weak. These are the traps I see most:

-

Undefined market: “Everyone who uses the internet” is not a market.

-

No time window: potential without “when” becomes fantasy.

-

One perfect number: I use ranges because inputs are uncertain.

-

Hidden adoption assumptions: adoption rate is where most bias hides.

-

Mixing units: customers, users, and revenue all blended together.

If I fix these, my market potential becomes a useful ceiling, not a story.

Conclusion

Market potential is the demand ceiling for a defined market, and I estimate it with clear boundaries and defendable ranges.