What Is A Business Case?

Projects fail when nobody can explain why the work matters. That chaos wastes time, money, and trust.

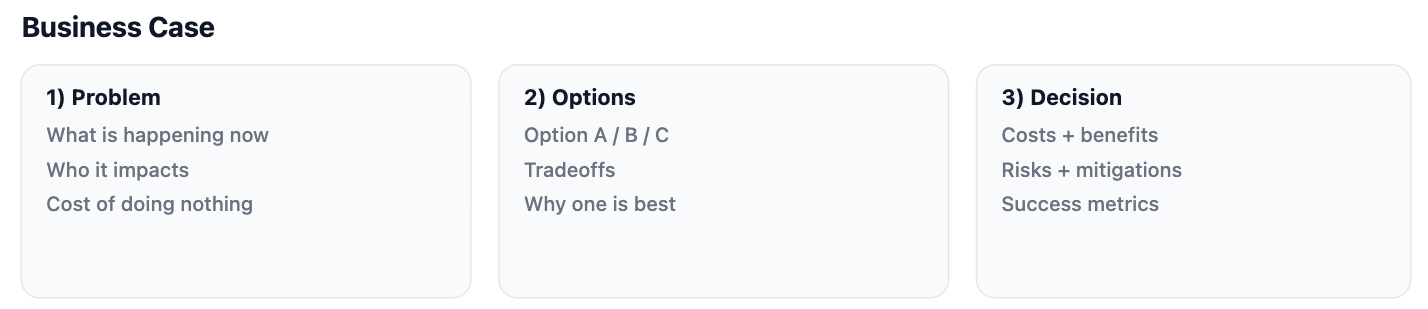

A business case is a short, structured document that explains why a project or decision is worth doing. It proves value, compares options, and defines what “success” means.

I use a business case as a clarity tool. It turns a vague idea into a decision people can support.

What Is A Business Case?

A business case is the reasoned argument for investing time, budget, and effort into a specific change. It is not a project plan, and it is not a pitch deck. It sits before delivery and answers the uncomfortable questions leaders will ask anyway: “What problem are we fixing?” “What happens if we do nothing?” “What will this cost?” “What will we gain?” “What could go wrong?” “How will we measure success?” When I write it well, it prevents “project drift,” where teams build stuff that feels busy but does not move outcomes.

I also treat a business case as a decision record. People forget why a project started. Teams change. Priorities shift. A clear business case helps me protect the original intent, or change it openly when the facts change. If I publish business content on voicesfromtheblogs.com, this is exactly the kind of topic I like, because it translates messy signals and opinions into a decision framework people can act on.

Why Do I Need A Business Case?

I need a business case because it aligns stakeholders and reduces risk before money and time are spent. Without it, projects often start based on excitement, politics, or anxiety. Then the real questions show up later, when it is expensive to change direction. A business case forces those questions early, when I can still choose a better option or tighten the scope. It also keeps teams honest about tradeoffs. Most projects have competing goals: speed vs quality, control vs flexibility, cost vs capability. The business case makes those tradeoffs visible, so I do not pretend everything is possible at once.

Here is what a good business case usually helps me do:

(1) Get approval faster because the logic is clear

(2) Avoid scope creep because “in scope” and “out of scope” are stated

(3) Choose the right option instead of defaulting to the loudest request

(4) Set success metrics so outcomes are measurable

(5) Defend priorities when new requests try to hijack the plan

If a project is small, I still use a light business case. If a project is large, I use a more detailed one. The principle stays the same.

What Should A Business Case Include?

A business case should include the problem, options, costs, benefits, risks, and a clear recommendation. I keep it structured so readers can scan it and still trust it. I also keep it short enough that people actually read it.

What Problem Am I Solving?

I define the problem in plain language and show why it matters now. I avoid vague statements like “we need a new system.” Instead, I describe the current pain: delays, errors, churn, missed revenue, or compliance risk. I include who is affected and how often it happens. If I can, I attach a simple baseline number, even if it is rough: hours wasted per week, conversion drop, support ticket volume, or error rate. I also write the “do nothing” path, because it anchors urgency. If doing nothing is cheap and safe, my business case should probably be smaller. If doing nothing is expensive and risky, the business case becomes easier to approve.

What Options Did I Compare?

I compare at least two options, including “do nothing,” so the decision is real. This is where many business cases fail. People write only one option, which turns the document into a justification instead of analysis. I list options at a level that matches the decision. For example: build vs buy vs outsource vs keep current and patch. Then I state the tradeoffs in simple terms: cost, speed, risk, and fit. I do not pretend one option is perfect. I show why one option is best for this context. That honesty increases trust.

What Are Costs, Benefits, And Risks?

I state costs, benefits, and risks with clear assumptions so the math can be checked. I separate one-time costs (setup, migration, training) from ongoing costs (licenses, maintenance, staffing). Then I list benefits in a way that maps to business goals: time saved, revenue gained, risk reduced, or customer experience improved. If I cannot quantify a benefit, I still describe it clearly, but I label it as qualitative. For risks, I list what could go wrong and how I plan to reduce it. A business case that ignores risk feels naive. A business case that lists risks with mitigations feels credible.

What Is The Recommendation And Plan?

I recommend one option and define what success looks like, plus the next steps. I include the decision I want, the budget I need, and the timeline at a high level. I also define success metrics up front, like: reduce cycle time by X, increase activation by Y, reduce defects by Z, or hit a compliance deadline. I keep it simple: 3–5 metrics max. Then I add a light plan: phases, owners, and checkpoints. This turns the business case into something leaders can approve and monitor, not just “agree with.”

How Do I Write A Business Case Step By Step?

I write a business case by starting with the decision, then filling in evidence and assumptions in a scan-friendly format. I do not start with a blank page. I start with a template and I keep it tight.

This is the sequence I use:

(1) Write the one-line decision: “Approve X to achieve Y by Z.”

(2) Define the boundary: what is included, and what is excluded.

(3) Describe the problem: current state, impact, and why now.

(4) List options: including “do nothing,” with simple tradeoffs.

(5) Estimate costs: one-time and ongoing, with assumptions.

(6) Estimate benefits: measurable first, then qualitative.

(7) List risks: top risks and mitigation steps.

(8) Define success metrics: 3–5 metrics with a baseline if possible.

(9) Add a high-level plan: phases, owners, timeline checkpoints.

(10) Finish with an executive summary: short and direct.

I also keep my language plain. If a reader needs to “decode” the business case, they will not approve it.

What Are Common Business Case Mistakes?

The most common mistakes are vague problems, fake numbers, and skipping options and risks. I avoid these because they destroy trust fast.

Mistakes I see often:

(1) No clear market or scope boundary so the project expands endlessly

(2) Only one option so it reads like a sales pitch

(3) Benefits without assumptions so the ROI feels made up

(4) Costs that ignore change effort like training and migration

(5) No success metrics so nobody can tell if it worked

(6) Too long and too dense so nobody reads it

(7) No owner so the business case is “everyone’s” and then no one’s

If I fix these, approval becomes easier, and delivery becomes calmer.

Conclusion

A business case explains why a project is worth doing, with options, tradeoffs, and clear success measures.