What Is Market Size?

Big ideas feel exciting, until someone asks, “How big is this market?” and I freeze.

Market size is the total demand for a market, usually measured as total customers or total revenue over a time period. I use it to prove the opportunity is real and to set targets that match reality.

I treat market sizing like signal decoding: I take messy market “voices” (buyers, competitors, pricing) and turn them into a number I can defend.

What Is Market Size?

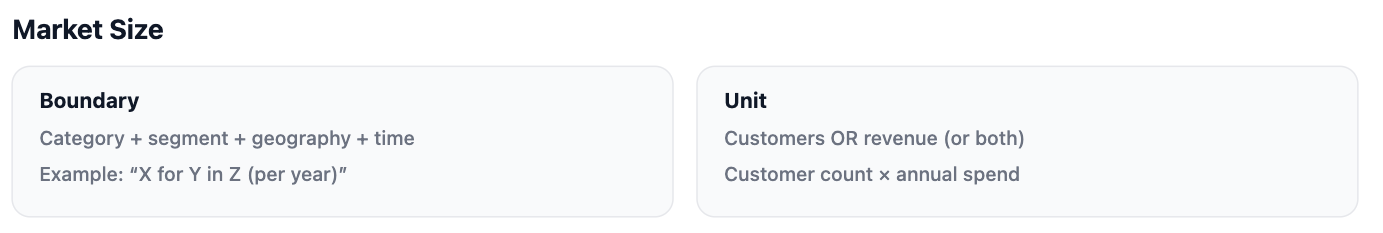

Market size is the total number of potential buyers or total spending available in a defined market. The definition sounds simple, but the key is the word defined. I always specify what market, where, for whom, and over what time period. If I do not, the number becomes meaningless. For example, “coffee” is not a usable market size for most businesses. “Specialty coffee subscriptions in the US for remote workers” is closer to something I can measure and act on. I also choose the right unit. Some markets are easier to size by customer count. Others are easier to size by dollars. I often write both, because it prevents confusion.

Here is how I define market size in a way that stays practical:

(1) Market boundary: category + segment + geography

(2) Customer unit: who counts as “one customer” (person, company, seat)

(3) Time window: annual is most common

(4) Spend unit: price per year, per month, or per transaction

If I cannot explain my boundary in one sentence, I know my market size will be inflated or vague.

Why Does Market Size Matter?

Market size matters because it shapes my strategy, my targets, and whether the business can support the effort. If the market is too small, I may cap out early even if I execute well. If the market is large but crowded, I may need sharper positioning and more budget to win. Market size also keeps me honest about growth plans. I have seen teams set goals based on excitement instead of math. Then they panic later when the funnel does not support the story.

I use market size to answer practical questions:

(1) Is the market big enough to build a real business?

(2) Which segment should I target first?

(3) What is a realistic revenue goal for year one?

(4) How much can I spend to acquire customers?

(5) How many customers do I actually need to hit the plan?

Market size also helps me communicate clearly. Investors, partners, and even internal teams want to know if the opportunity is “niche-small,” “healthy,” or “massive.” When I size the market with clear assumptions, I reduce argument and increase focus. That is the same reason I like “signal-first” thinking: numbers become a shared language when the inputs are visible.

How Do I Calculate Market Size?

I calculate market size by choosing a method and stating assumptions clearly so the math can be checked. I do not aim for fake precision. I aim for a number that is directionally right and defensible. I usually use one of three methods: top-down, bottom-up, or value theory. I prefer bottom-up when I can, because it is easier to tie to real customers and pricing.

What Is The Top-Down Method?

Top-down market sizing starts with a published market number and narrows it using filters. This is fast, but it can be sloppy if I filter with weak logic. If I use top-down, I make the filters explicit. For example, I might start with a large category number, then narrow by geography, then narrow by segment, then narrow by channel fit. The risk is that I can “filter my way” into any number I want. So I keep the filters conservative and I sanity-check against reality. If the final number implies an impossible customer count, I know I am fooling myself.

What Is The Bottom-Up Method?

Bottom-up market sizing builds the market from real units: customers × price (or transactions × price). This is my default because it forces me to define who the buyer is and what they pay. A clean bottom-up structure looks like this:

(1) define the customer unit (one company, one household, one seat)

(2) estimate how many units exist in my defined boundary

(3) estimate realistic annual spend per unit

(4) multiply to get annual revenue potential

If I am doing B2B, I might use: number of target companies × average contract value. If I am doing B2C subscriptions, I might use: number of target households × annual subscription price. Bottom-up also makes it easier to connect market size to go-to-market capacity. If my market size assumes 500,000 buyers, but my channel can only reach 5,000 well, I know I need a better plan or a tighter segment.

What Is Value Theory?

Value-theory sizing estimates market size based on the value created and what share of that value customers will pay. I use this when pricing is not standard or when the product creates a measurable financial outcome. For example, if my product saves a business $100,000 per year, and buyers commonly pay 10% of saved value, that implies a pricing ceiling of $10,000 per year per customer. Then I multiply by the number of customers that have that problem. This method can be powerful, but it requires careful assumptions. If I exaggerate value, the market size becomes fantasy. I keep it grounded by using conservative value estimates and real proof where possible.

What Are Common Market Size Mistakes?

The most common market size mistakes are using vague boundaries, confusing audience size with spending, and hiding assumptions. I see these errors repeatedly, and they make otherwise good plans look weak.

Here are the mistakes I actively avoid:

(1) Sizing “everyone” instead of a real segment

(2) Using population numbers without purchase intent

(3) Using TAM as if it is reachable revenue

(4) Assuming perfect conversion and perfect distribution

(5) Picking a number first, then backfilling logic

(6) Mixing methods without explaining the bridge

(7) Not stating time period (monthly vs annual confusion)

My quick sanity checks are simple:

(1) does the implied customer count make sense?

(2) does the implied spend per customer match reality?

(3) does my go-to-market plan have a believable path to reach even a small share?

If my number fails those checks, I rewrite it.

How Do I Present Market Size In A Business Plan?

I present market size with a clear boundary, one method, and a short assumptions list so readers can trust the logic. I keep it tight. I do not dump pages of math. I show the core calculation and the source of each input. The goal is not to “win the biggest number.” The goal is to show I understand the market.

This is the format I use:

(1) Market definition (one sentence): who, what, where, time

(2) Method: top-down or bottom-up (state which)

(3) Core calculation: one line of math

(4) Assumptions: 3–6 bullets

(5) What it means: how it shapes strategy and targets

When I write it this way, the market size becomes useful. It stops being decoration and starts becoming a decision tool.

Conclusion

Market size is the total demand in a defined market, and I estimate it with clear boundaries, simple math, and honest assumptions.